A proposal to extend fixed-rate mortgages to 50 years creates an immediate headline: lower monthly payments and broader qualification. For buyers in Utah, where housing markets range from multimillion-dollar ski-town estates to entry-level suburban homes, the policy would not change housing affordability in a vacuum. Instead, it would change incentives, pricing dynamics, and wealth transfer across generations. This analysis breaks the math down, shows the amortization realities, models what happens if the monthly savings are invested, and explores practical strategies for Utah buyers, sellers, and investors given the unique local market factors.

Executive summary

Stretching a mortgage term from 30 years to 50 years reduces monthly payments but increases the total interest paid dramatically. Using a conservative scenario centered on a $400,000 loan at a 6 percent fixed interest rate provides an apples-to-apples comparison. In that scenario, the monthly payment drops by roughly $292 per month when moving from a 30-year to a 50-year term. That drop can ease monthly cash flow immediately, but over decades the borrower pays hundreds of thousands more in interest. If the monthly savings are invested and compounded consistently, an investor could build a substantial nest egg—but only under optimistic assumptions about investment returns, taxes, inflation, and personal discipline.

For Utahans, this trade-off is complicated by elevated home prices in many parts of the state, wide variation by city, and a meaningful property tax burden in some jurisdictions. The policy would alter market demand across Utah cities, likely pushing prices higher where buyers previously failed underwriting because of monthly-payment constraints. Policymakers, lenders, developers, and homebuyers all have incentives that differ from the household that wants real wealth accumulation rather than a temporary cash-flow fix.

How the 50-year mortgage headline became a national talking point

Proposals to extend the length of fixed-rate mortgages are often framed as increasing access to homeownership by lowering monthly payments. This can be true at the individual level: stretching principal across more payments reduces monthly principal and interest. But that reduction is not free. It shifts costs into the future and amplifies the total interest burden. The larger economic effect is an increase in demand for homes at a given income level, which pushes sale prices higher. In the Utah context—where markets from Salt Lake City to Park City show divergent pricing dynamics—this would not evenly distribute benefits.

Three immediate questions must be asked when evaluating a long-term mortgage innovation:

- Who obtains the immediate benefit of lower monthly payments?

- Who pays the long-run cost of extended interest accrual?

- How do lenders and developers respond to increased buyer qualification capacity?

These questions are essential for anyone searching for property in Utah, whether first-time buyers in St. George or investors looking at Salt Lake City rentals.

Baseline scenario: the math behind 30-year versus 50-year at 6 percent

To compare terms transparently, consider a fixed-rate mortgage with the following inputs that match common market examples:

- Loan amount: $400,000

- Interest rate: 6.0 percent (fixed)

- Term A: 30 years (360 months)

- Term B: 50 years (600 months)

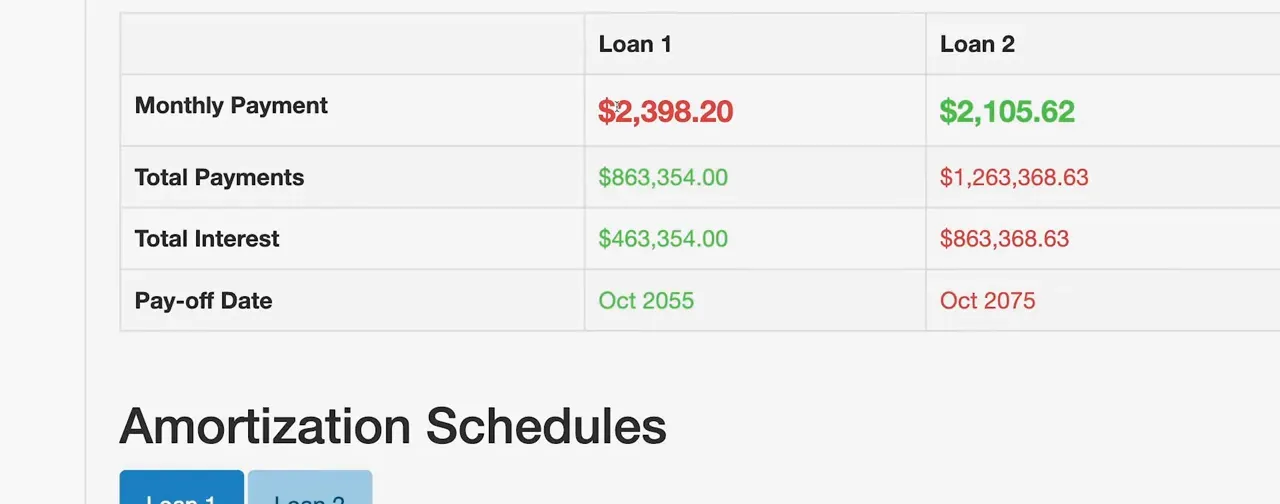

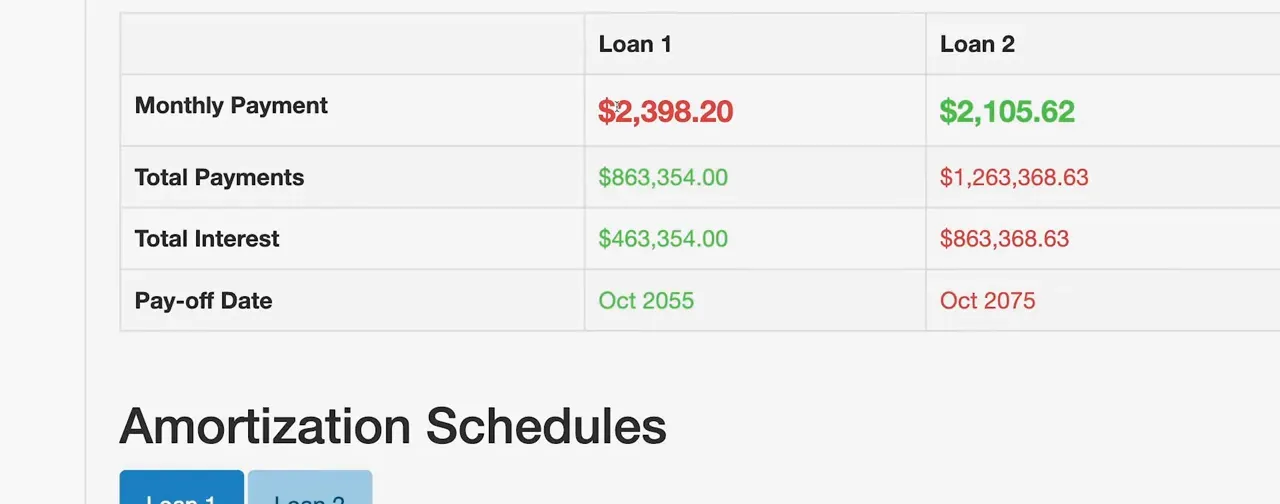

Using standard mortgage formulas, the monthly payment for the 30-year loan equals roughly $2,398. For the 50-year loan, that same principal and rate yields a monthly payment of approximately $2,105. The monthly cash-flow improvement when switching to 50 years is therefore about $292.58 per month.

Those monthly payment figures translate into vastly different totals paid over time:

- 30-year mortgage total payments: roughly $863,000 (principal plus interest)

- 50-year mortgage total payments: roughly $1,260,000 (principal plus interest)

That is a difference of nearly $397,000 in nominal dollars over the life of the loan—almost another entire mortgage on top of the original principal. Even when adjusting for inflation that difference remains meaningful in today’s dollars.

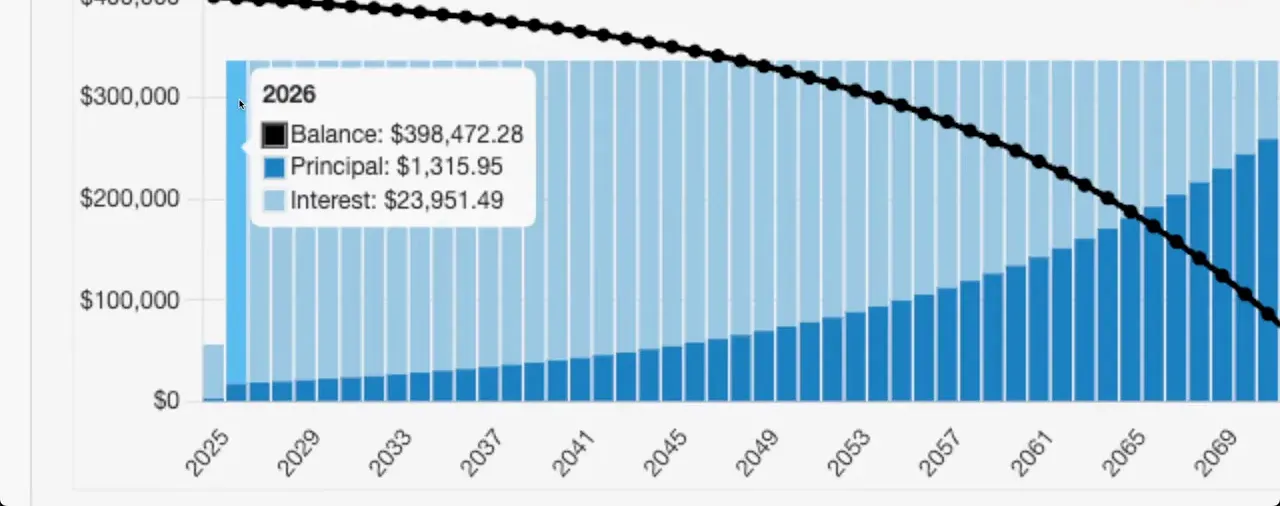

Amortization explained: why early payments barely touch principal

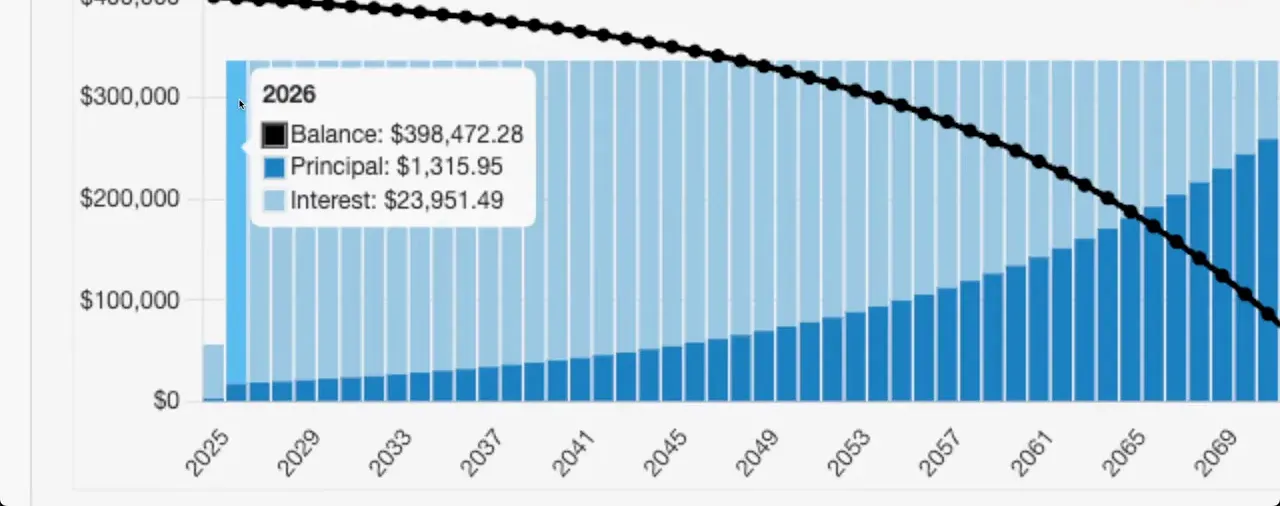

Amortization schedules show how each monthly payment divides between interest and principal. Mortgages are front-loaded with interest: early payments cover almost entirely interest and only a small fraction of principal. That is true for both 30-year and 50-year fixed-rate loans, but the effect becomes starker as term lengthens.

Year-one comparisons illustrate the difference concretely:

- 30-year loan year-one: approximately $4,961 applied to principal and $24,000 applied to interest. That means about 17.2 percent of the year-one payment went toward principal reduction.

- 50-year loan year-one: approximately $1,315 applied to principal and $24,000 applied to interest. That means only about 5 percent of the year-one payment went toward principal reduction.

These percentages are not trivial. For the 50-year mortgage, two-thirds or more of early decade payments functionally rent a household’s occupancy rather than build equity. After 30 years on a 50-year schedule the balance remains close to the original principal. Equity accumulation becomes extremely slow unless the homeowner makes extra principal payments, refinances, or market appreciation does the work.

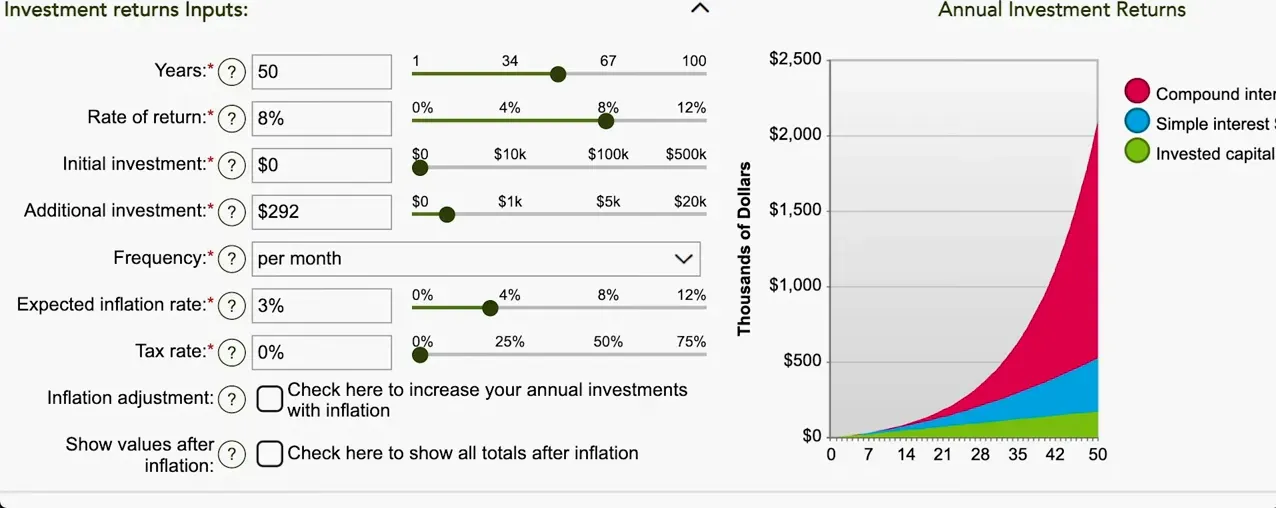

Invest the difference? Modeling the “invest the monthly savings” argument

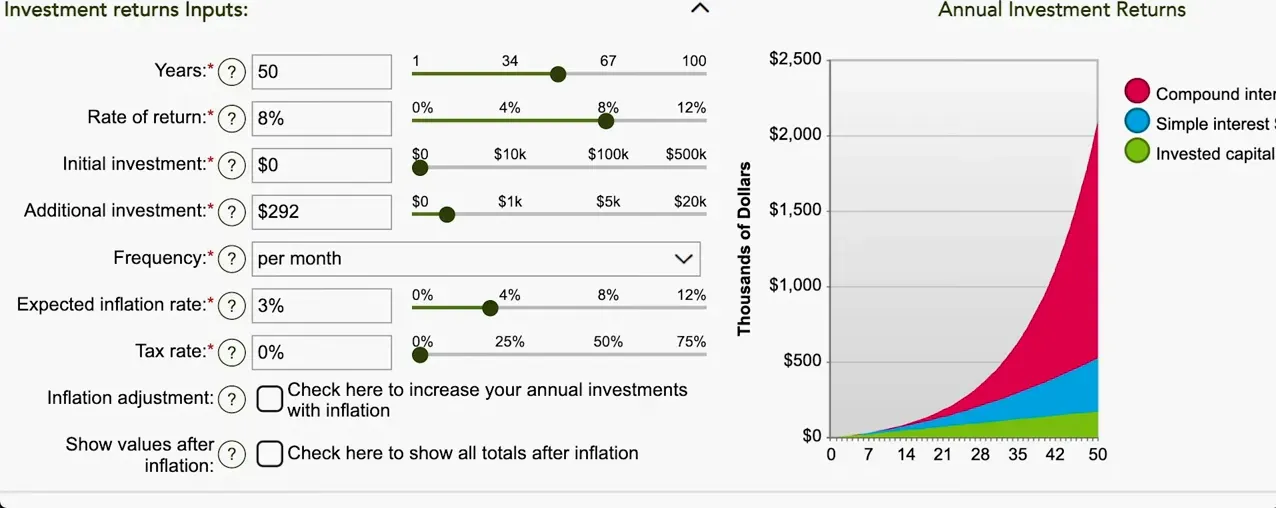

Proponents of longer mortgages often argue that the monthly savings should be invested. If households consistently invest the payment delta, compounding can produce meaningful wealth. Real outcomes depend on several variables, including expected return, tax treatment, inflation, and discipline. The example below demonstrates a realistic but optimistic scenario that helps clarify trade-offs.

Scenario:

- Monthly savings invested: $292.58

- Investment return: 8.0 percent nominal annual return (historically conservative for long-term stock returns depending on timeframe)

- Time horizon: 50 years

- Inflation assumed for real purchasing-power adjustment: 3.0 percent annually

- Taxation: model assumes investment grows in taxable or tax-advantaged vehicles but simplifies taxes by focusing on nominal and inflation-adjusted results

With $292.58 invested monthly for 50 years compounded at 8 percent per year, the nominal account value at the end of the period is roughly $2.1 million. Nominal compound interest builds more than $1.9 million beyond invested capital due to the power of long-term compounding.

However, a dollar in year 50 is not the same as a dollar today. Adjusting the nominal result for a 3 percent annual inflation rate reduces the purchasing-power equivalent of that $2.1 million substantially. In the scenario above, the inflation-adjusted value is roughly $500,000 in today’s dollars. Subtracting the inflation-adjusted value of the invested capital (the contribution stream) yields net gains in the neighborhood of $430,000 in today’s purchasing power, assuming the household had the discipline to invest each month for five decades and the return assumptions hold.

Two key caveats appear immediately:

Explore Utah Real Estate

653 E RYEGRASS DR #305, Eagle Mountain, UT

$387,900

Bedrooms: 3 Bathrooms: 3 Square feet: 1,985 sqft

6668 S 3200 W, Spanish Fork, UT

$2,199,999

Bedrooms: 3 Bathrooms: 3 Square feet: 2,560 sqft

1500 FISH CREEK RD, Bancroft, ID

$1,100,000

Bedrooms: 6 Bathrooms: 4 Square feet: 3,767 sqft

- Behavioral risk. Households seldom consistently invest every month for 50 years. Life shocks, shifting priorities, and liquidity needs frequently interrupt disciplined investing.

- Market risk and sequence of returns risk. The assumed 8 percent return is an average; markets can deliver long periods of low or negative real returns, especially over decades if the economy experiences stagnation or flat returns similar to Japan’s multi-decade equity performance in some scenarios.

What this math means for Utah buyers

Utah’s housing markets are heterogeneous. Average and median prices vary widely between counties and metro areas. For many Utah buyers, the limiting factor in home purchase capability is monthly payment, not long-term interest cost. Extending mortgage terms expands the set of homes that fall within monthly-budget constraints even if the long-run cost grows.

Three direct implications for Utah residents:

- Demand compression into desirable micro-markets will increase. When monthly payments are the primary gatekeeping metric, higher-amenity neighborhoods—good schools, proximity to employment centers, and outdoor recreation—become affordable to more buyers, which bids prices higher and compresses value-per-dollar.

- Developers and lenders can adjust pricing and product offerings to capture the increased buying power. That dynamic tends to favor sellers and project-level profit rather than first-time buyers.

- Property tax exposure remains. A paid-off mortgage does not eliminate property taxes and other carrying costs. In many Utah jurisdictions, property taxes, HOA fees, insurance, and maintenance are real annual expenses that shape net wealth even after loan principal is eliminated.

Consider the sample regional snapshots that reflect the variety of Utah markets. These are illustrative categories that echo common listing price data across northern and southern Utah:

- Park City and Heber Valley: high-end ski and resort markets with average listing prices often well above $2 million in desirable neighborhoods. Buyers here often rely on wealth rather than mortgage leverage, but the pricing sensitivity can ripple across second-home buyers and rental markets.

- Salt Lake City and South Jordan: urban and suburban markets with strong employment centers, tech and healthcare hubs, and significant demand among young professionals. Price growth here accelerates when buyers can qualify for larger loans via stretched terms.

- St. George and southern Utah: rapid population inflow and amenity demand have increased average listing prices and created a strong investor rental market in retirement-friendly climates.

- Smaller cities and exurban areas: more affordable entry points exist, and stretching terms would enlarge buyer capacity. However, the trade-off often moves affordability pressure into high-demand corridors rather than creating new affordability overall.

This heterogeneity matters. A 50-year mortgage that looks attractive in Cedar City may have different second-order effects in Park City. The policy’s net effect on affordability must therefore be assessed at block, city, and region levels rather than as a single aggregated national metric.

Property taxes, carrying costs, and the illusion of ownership

Owning a home extends beyond mortgage principal. In Utah, property taxes vary by county and municipality, and combined carrying costs—including insurance, maintenance, HOA dues, utilities, and periodic capital expenses—can be financially meaningful. A homeowner whose mortgage remains outstanding for decades may pay less per month in mortgage principal initially with a 50-year structure but will continue paying recurring carrying costs indefinitely.

For many households, the end-state ideal of “paid-off” property no longer guarantees financial freedom. Even when mortgage principal disappears, property taxes remain, and those taxes often rise. If a household’s long-term objective is wealth accumulation, the purchase decision should weigh the interest paid over the loan term plus the ongoing tax and maintenance costs against alternative uses for that capital.

An example: a suburban homeowner with a paid-off property paying $10,000 per year in combined property taxes and insurance experiences an annual carrying cost similar to a rental in some markets. The existence of a mortgage does not eliminate this reality. Extended mortgage terms postpone principal repayment and might reduce monthly mortgage payments, but they do not reduce other escalating costs over a multi-decade horizon.

Winners, losers, and market incentives

Understanding the incentives clarifies why policy shifts matter:

- Potential winners

- Short-term buyers who need immediate monthly relief and plan to move or refinance before paying significant extra interest.

- Developers who can sell higher-priced homes to buyers who qualify under stretched-term underwriting.

- Banks that collect interest for longer horizons and possibly securitize elongated mortgage streams.

- Potential losers

- Long-term home buyers seeking to build equity quickly—particularly those who cannot or will not invest monthly savings disciplinedly.

- First-time buyers competing in markets where developers and existing owners increase prices because qualification ceilings expanded.

- Families on fixed incomes who bear rising property taxes regardless of mortgage term.

The net distribution of benefits depends on behavior. If buyers use monthly savings to purchase durable consumption goods rather than invest, the benefit is transient and largely benefits sellers and lenders as prices rise. If disciplined investing occurs, households can capture value—but that discipline is a behavioral hurdle for many, especially in regions with high living costs where emergency liquidity needs arise.

Practical buying strategies for Utah residents considering long-term mortgage offers

For Utah buyers weighing a 50-year mortgage versus a conventional 30-year, several practical strategies can mitigate long-run costs while preserving near-term affordability.

1. Consider a fixed-rate with an aggressive amortization plan

A borrower can take a longer-term mortgage for the flexibility of lower mandatory payments while committing to an internal amortization schedule consistent with a shorter-term loan. Simple practices include making extra principal payments equal to the difference between the 30-year and 50-year monthly amounts or doubling up one payment per year. In many cases lenders allow extra principal payments without penalties. This hybrid approach retains monthly flexibility but accelerates equity build-up when finances permit.

2. Use temporary term extension strategically

If the reason for a 50-year term is temporary hardship—job transition, young family budget—the goal should be to refinance to a shorter term when the household’s financial situation stabilizes. Refinancing creates its own costs and relies on future rates being favorable, but it is a valid strategy for households expecting stable income growth or improved balance sheets.

3. Buy less house than maximum qualification

Underwriting that stretches based on monthly-payment metrics encourages buyers to maximize loan amounts. Wealth-building buyers should question the “affordability” calculation and prefer a purchase that leaves room for investing or an emergency buffer. This trade-off is especially relevant in Utah markets where land and location premiums can inflate purchase prices markedly.

4. Factor in carrying costs and local taxes

Utah buyers must model taxes, HOA dues, and ongoing maintenance into affordability decisions. The nominal mortgage payment may look manageable but adding $5,000 to $15,000 per year in carrying costs changes net monthly affordability. A comprehensive cash-flow model prevents surprise expenses later.

5. Evaluate investment alternatives realistically

If the plan is to invest monthly savings, run multiple market-return scenarios, consider tax treatment, and include rollover risks. Building a separate emergency fund before committing to long-term investing is essential because drawing down invested capital to meet family needs undermines compounding benefits.

What to expect from refinancing, and why many households refinance anyway

One of the pragmatic realities of mortgage markets is that many borrowers refinance at least once in their homeownership lifecycle when interest rates drop or when they need to tap equity. A 50-year loan increases the option value of refinancing but also prolongs the period during which refinancing provides benefit. A borrower with long-term plans to remain in a home will often find that making extra principal payments early and then refinancing to a shorter term when rates allow is more cost-effective than staying on an elongated schedule for decades.

More Properties You Might Like

86 S 950 E, Hyde Park, UT

$774,900

Bedrooms: 6 Bathrooms: 4 Square feet: 3,544 sqft

LOOKING GLASS RD, La Sal, UT

$998,100

Bedrooms: 3 Bathrooms: 1 Square feet: 792 sqft

216 W RIDGE RD, Saratoga Springs, UT

$309,999

Bedrooms: 3 Bathrooms: 2 Square feet: 1,196 sqft

Policy risks and systemic consequences

Longer mortgage terms are not neutral policies. They change macro-level incentives, increase systemic debt service obligations, and potentially create asset-price inflation. Policy makers considering term extensions should anticipate market responses: lenders might offer more creative credit products, developers might shift supply to maximize revenues from newly qualified buyers, and price appreciation could accelerate, pushing affordability to workers who cannot participate due to lack of savings or poor credit.

There is also a public finance dimension. If extended terms become widespread and household net wealth is concentrated in illiquid home equity that accumulates slowly, then intergenerational wealth transfer changes. Younger generations could enter the workforce already priced out of local markets that enjoyed real affordability in earlier decades. This has implications for workforce distribution, regional competitiveness of Utah cities, and the political economy of housing policy.

Scenario narratives: how different Utah households fare under a 50-year option

Scenarios help contextualize numeric trade-offs.

Scenario A — Young professional, Salt Lake City

A software engineer qualifies for a larger home under a 50-year structure due to lower monthly payment. The engineer gains better commute and neighborhood amenities but accepts a higher total interest cost over the decades. If the engineer invests the monthly savings consistently and the tech wage rises with inflation, long-term outcomes could be positive. However, if a recession triggers several years of job instability, the long amortization may leave the engineer with slow equity growth and limited mobility.

Scenario B — Family in a suburban school district

A family with school-aged children chooses a 50-year mortgage to reduce monthly strain. The family values current living standards over long-run interest minimization. If prices in their district rise due to increased demand, the family’s home may appreciate, partially offsetting interest costs. But rising property taxes and maintenance can compress household budgets as children age into college and other expenses grow.

Scenario C — Long-term investor in St. George

An investor buying a rental property may use a 50-year mortgage to increase cash flow margin and operate the asset as a cash-flowing property. The investor’s return depends on rental growth, cap rates, and maintenance. For investors with diversified portfolios and multiple assets, elongation of mortgage terms can be an operational advantage if total return expectations outpace the cost of the loan.

Behavioral economics: why most households do not invest the monthly difference

Arguing that households will invest monthly savings assumes a high level of financial discipline. Behavioral studies and historical observations of consumer finance indicate that many households treat monthly budget improvements as increased spending capacity rather than systematic savings. Tax refunds, bonuses, and monthly windfalls are often consumed rather than saved. For this reason, the theoretical advantage of investing monthly mortgage savings may not materialize for the majority of buyers unless accompanied by automatic investment mechanisms such as payroll deductions or automatic transfers to retirement or brokerage accounts.

Regulatory and moral considerations

Some critics of extended mortgage terms frame the debate in moral terms. Concerns about usury, consumer exploitation, and rent-seeking behavior appear in public discourse. The ethical arguments often focus on whether policies that make ownership appear affordable are genuinely helping households build wealth or simply prolonging indebtedness. For policymakers and consumer protection agencies, transparency about long-term interest costs and required disclosures about total cost of credit become paramount if elongated terms gain wide acceptance.

One-page checklist for Utah home shoppers evaluating a long-term mortgage

- Run an amortization comparison between 15, 30, and proposed 50-year terms at realistic rates for the market.

- Calculate total interest cost over the relevant horizon and compare that to alternate uses of the monthly savings.

- Estimate annual carrying costs in the target Utah jurisdiction, including property tax, insurance, HOA dues, and maintenance.

- Model investment outcomes under conservative, median, and optimistic return scenarios if planning to invest the monthly savings.

- Consider flexibility: is the household likely to refinance in 5 to 10 years if rates fall or income grows?

- Set up automatic investment mechanisms if the intention is to invest monthly savings, to reduce behavioral leakage.

- Ask whether buying less house aligns better with long-term net worth goals than stretching for more house via longer terms.

Where Utah cities fit into the new affordability equation

Different Utah markets will respond to stretched underwriting in varied ways. High-demand, amenity-rich markets will likely experience price acceleration as buyers with marginal qualification move into them. More affordable exurban and rural markets could absorb increased demand without the same price spike, but local infrastructure and tax capacity will determine how sustainable that growth becomes.

Examples of city-level effects to watch:

- Park City and Heber: luxury and second-home market dynamics; a small number of elevated buyers can alter local service economies and rental stock.

- Salt Lake City and South Jordan: demand from professionals could push inventory down and prices up, affecting first-time buyers and renters.

- St. George and southern Utah: in-migration trends may intensify, and investor appetite could turn single-family rentals into investor plays, altering neighborhood composition.

- Smaller markets: potential for improved accessibility for families but local wage growth and job availability will determine long-term sustainability.

External resources and further reading

For Utah-specific data on housing, population trends, and regulatory guidance, consult authoritative sources such as the Utah state portal and national real estate associations. Local county assessor offices provide property tax rates and parcel-specific information that is crucial for carrying cost calculations. For national mortgage and macro data, consult federal statistics and mortgage-market reporting to stay informed about prevailing interest rates and loan product availability.

Authoritative resources to consider include utah.gov and nar.realtor for national market context.

Visit https://bestutahrealestate.com for local listing and market information tailored to Utah buyers and sellers.

Final thoughts: policy, prudence, and location-specific strategy

Extending mortgage terms to 50 years is not a silver bullet for housing affordability. For Utah residents, the policy would have asymmetric effects across cities, neighborhoods, and demographic groups. The math is straightforward: longer terms reduce monthly burden but dramatically raise total interest costs. Investing the monthly savings can generate substantial nominal gains if markets deliver strong long-term returns and if household behavior is disciplined. Yet behavioral realities and local tax and maintenance burdens complicate the picture.

Practical advice for Utah buyers centers around careful analysis and conservative planning. Buyers should run amortization tables, incorporate realistic carrying-cost estimates for the target municipality, and develop a disciplined plan for any monthly savings—preferably automated—to avoid consumption leakage. When possible, buyers seeking wealth accumulation should consider purchasing conservatively relative to maximum qualification, accelerate payments when feasible, and treat homeownership as one element of a diversified financial plan.

Policy discussions require attention to system-level incentives. If mortgage-term extensions become widely available, regulators and housing policymakers should monitor price dynamics, ensure transparent disclosures about total loan cost, and consider complementary policies that address supply-side constraints rather than only widening credit availability. Only a combined approach that addresses supply, demand, taxes, and borrower education will produce durable improvements to affordability in Utah’s diverse housing markets.

Utah’s housing future will be shaped by how buyers, lenders, and policymakers react to credit changes. Households that prioritize long-term net worth will treat mortgage-product innovation with skepticism and plan accordingly. Those that need immediate relief may welcome longer terms but should do so understanding the long-run cost and the alternatives available.

Frequently asked questions

Closing note

Choosing the right mortgage is a deliberate financial decision. For Utah buyers, that decision should weigh local market conditions, property taxes and carrying costs, behavioral tendencies regarding savings, and long-term wealth goals. When the headlines promise lower monthly payments, the deeper question remains unchanged: does the structure increase a household’s long-run net worth or simply shift costs into the future while enriching sellers and lenders today? The prudent course is to analyze scenarios, remain disciplined, and align housing choices with broader financial objectives rather than monthly convenience alone.

Frequently Asked Questions

How much would monthly payments change for a typical Utah mortgage if the term extended to 50 years?

For a $400,000 loan at 6 percent interest, monthly principal and interest would decline from roughly $2,398 for a 30-year mortgage to about $2,105 for a 50-year mortgage, a drop of approximately $292 per month. The exact change for any borrower depends on the loan amount, interest rate, and local market conditions. In Utah markets with higher median prices, the dollar reduction may not be sufficient to make drastically more expensive neighborhoods accessible unless combined with other shifts like increased income or decreased down payment requirements.

Does a 50-year mortgage mean a borrower will pay less overall for the house?

No. A 50-year mortgage reduces monthly payments but increases total interest paid. In the $400,000 at 6 percent example, total payments over 30 years are roughly $863,000 versus roughly $1,260,000 over 50 years. The borrower pays significantly more in nominal dollars when choosing a longer term unless offset by future refinancing or substantial investing returns produced by the monthly savings.

Will extending mortgage terms make housing more affordable in Utah?

Not necessarily. Extended terms can increase nominal affordability by lowering monthly payments, but they also increase buyer purchasing power and therefore can push sale prices higher. In many Utah markets, the net effect could be higher prices rather than improved long-term affordability. The policy will redistribute burden across time and households but does not automatically reduce the real cost of housing.

What are practical alternatives to a 50-year mortgage for Utah buyers who need lower monthly payments?

Alternatives include buying a smaller or less expensive home, selecting a 30-year or 15-year mortgage and using extra payments only when feasible, pursuing a loan with an adjustable-rate period that starts lower (with caution), using biweekly payments to accelerate amortization, or negotiating seller concessions to offset closing costs or initial carrying expenses. Additionally, seeking down payment assistance or grants specific to Utah programs can reduce principal and therefore monthly payments without increasing term length.