A proposal to extend mortgage terms to 50 years may sound like a straightforward way to lower monthly payments, but the numbers tell a different story. For Utah homebuyers and sellers, a 50-year mortgage would change affordability calculations, increase lifetime interest costs, and introduce systemic risks to lenders and investors. This article explains the history of the 30-year mortgage, the math behind amortization, why a 50-year term offers minimal affordability gains, and what practical policy changes would better unlock Utah housing inventory.

The origin of the 30-year mortgage and how amortization works

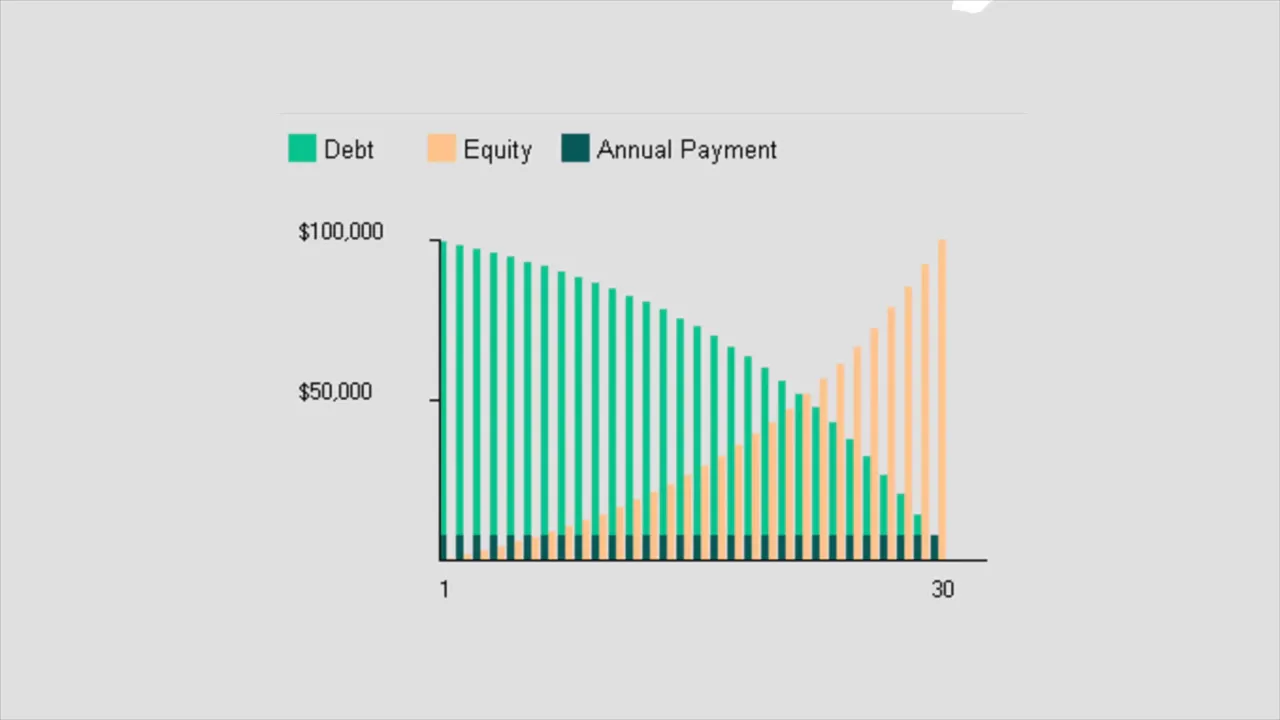

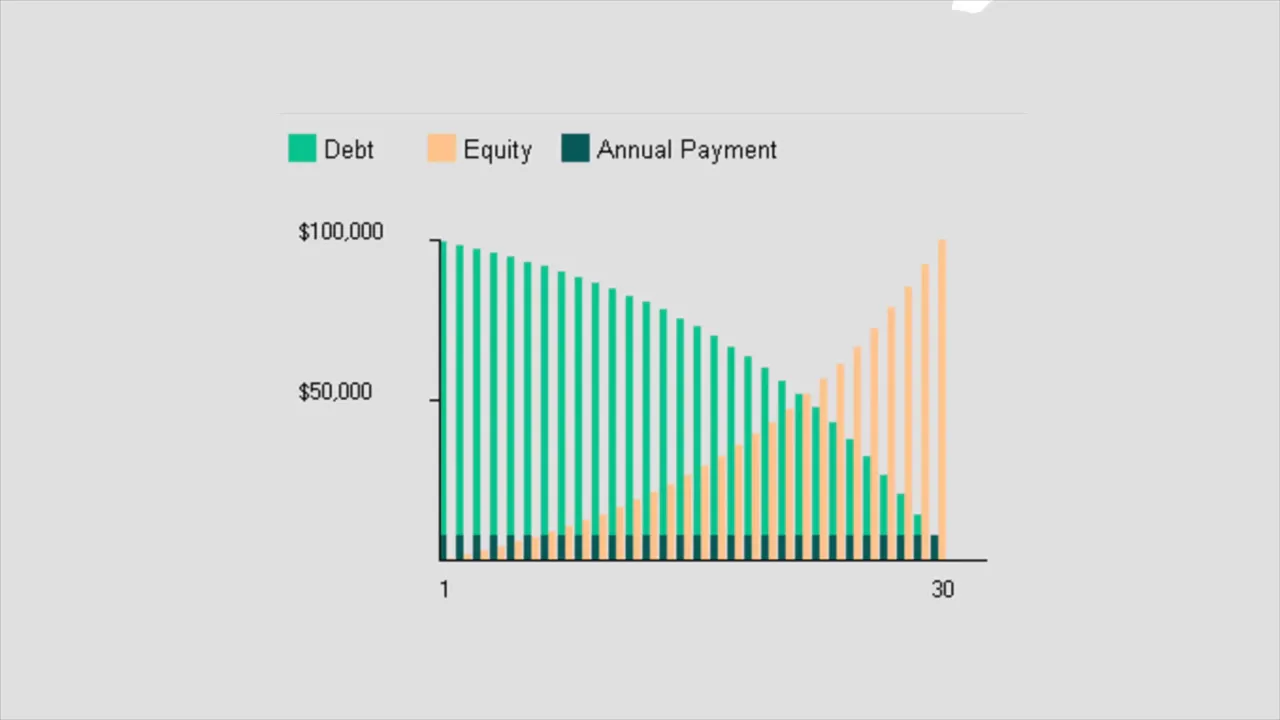

The 30-year mortgage became widespread after World War II to finance new construction and help families build long-term equity. It remains the dominant loan term because it balances manageable monthly payments with predictable amortization. Each fixed-rate mortgage payment splits into principal and interest. Early in the loan most of the payment goes toward interest, and little principal is paid down. Over time the allocation shifts and payments increasingly reduce principal, accelerating equity accumulation.

Because the average homeowner sells after roughly 12 years, many borrowers have paid very little principal before moving and starting a new loan. That behavioral pattern is central to why mortgage-backed securities and the secondary market function as they do. The amortization schedule matters: a long-term loan pushes principal paydown decades into the future.

Why a 50-year mortgage looks attractive but fails the math

Stretching a loan from 15 to 30 years increases purchasing power substantially: roughly a 34 percent improvement in affordability. Stretching from 30 to 50 years, however, yields far smaller gains—about an 8 percent boost in qualification power in realistic scenarios. The reason is simple: once payments become long-term, additional years add little incremental affordability because interest remains a large share of every payment for an extended period.

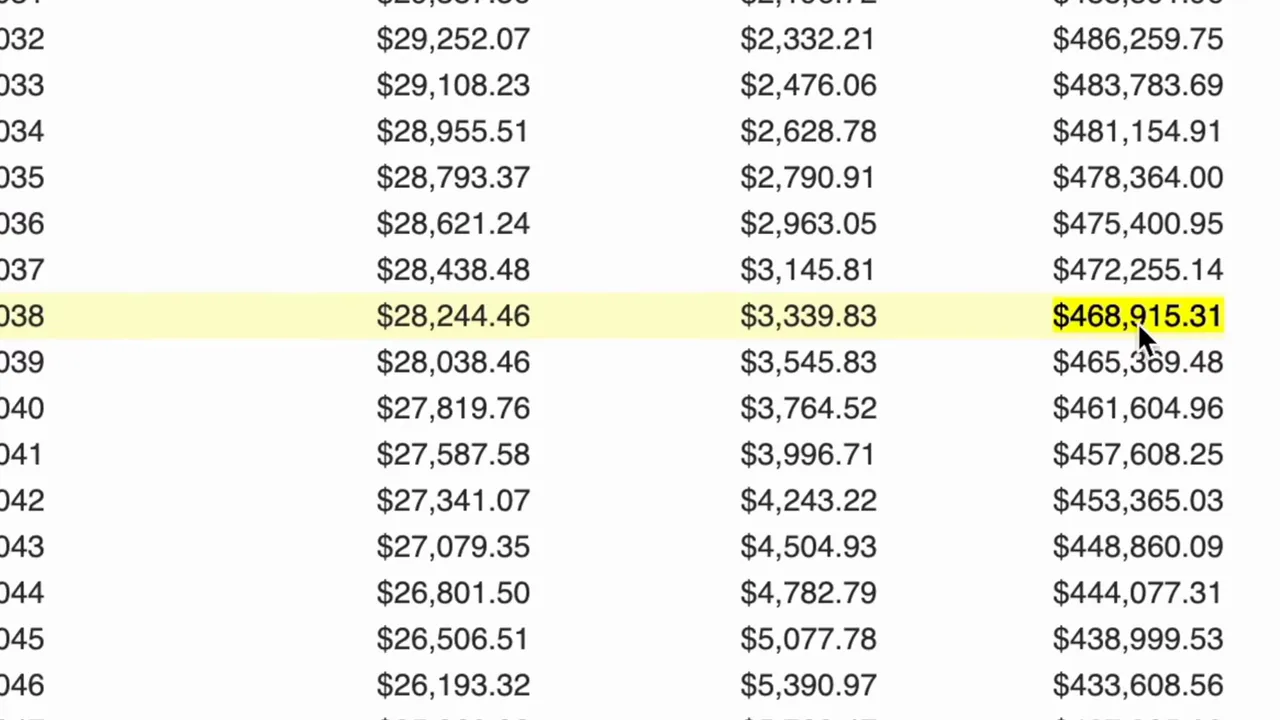

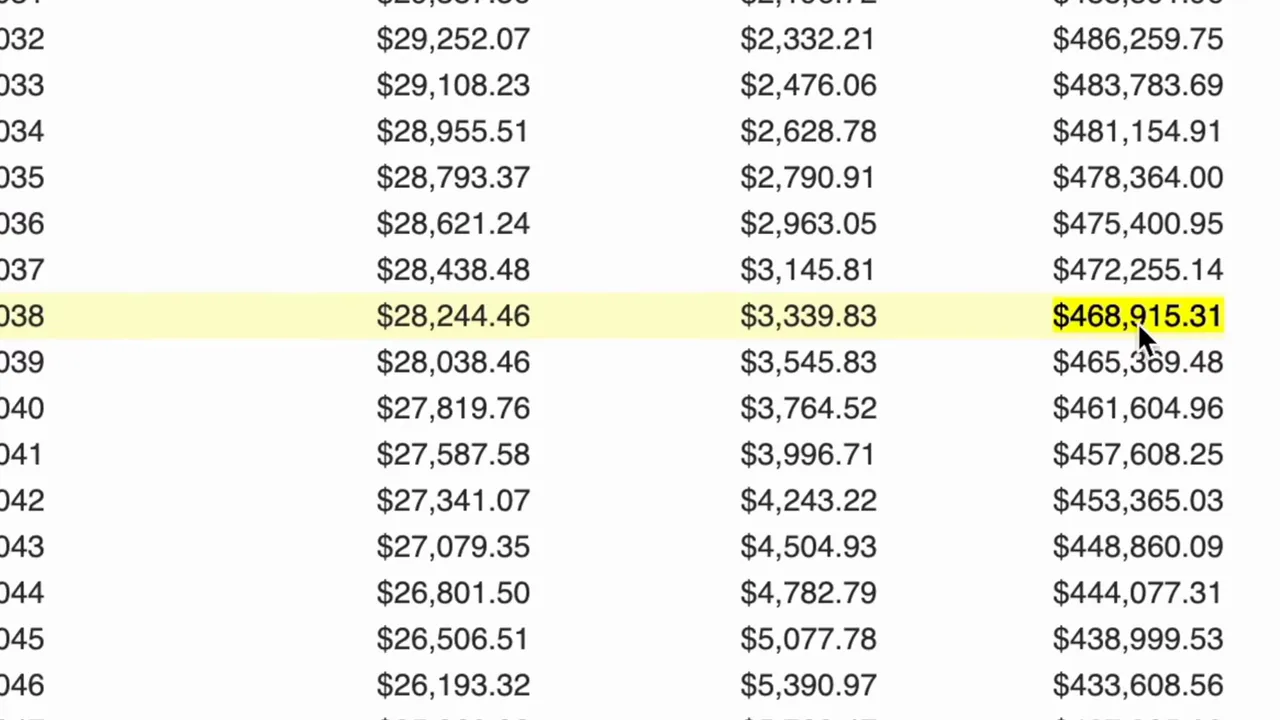

Interest-rate expectations further undermine the 50-year pitch. Lenders price longer terms higher to compensate for greater risk. If a 30-year fixed rate sits near 6.125 percent and a 15-year rate is around 5.375 percent, a plausible 50-year rate would be closer to 7 percent. On a $500,000 loan, a 30-year loan at 6 percent produces monthly payments around $3,000. Stretching to 50 years at a higher 7 percent could actually raise monthly payments rather than lower them. Even in a hypothetical where a 50-year carries the same rate as a 30-year, the monthly payment falls only modestly—to about $2,632 in one common example—equating to roughly a 10 percent effective increase in buying power. That modest benefit does not justify decades more interest paid and the added risk of minimal equity accumulation for many years.

Explore Utah Real Estate

653 E RYEGRASS DR #305, Eagle Mountain, UT

$387,900

Bedrooms: 3 Bathrooms: 3 Square feet: 1,985 sqft

6668 S 3200 W, Spanish Fork, UT

$2,199,999

Bedrooms: 3 Bathrooms: 3 Square feet: 2,560 sqft

1500 FISH CREEK RD, Bancroft, ID

$1,100,000

Bedrooms: 6 Bathrooms: 4 Square feet: 3,767 sqft

Investor, secondary market, and systemic risks

Mortgage rates are closely tied to the 10-year Treasury yield because most homeowners hold a mortgage for roughly a decade before selling or refinancing. That behavior allows lenders and investors to expect reasonably consistent prepayments and cash flow. A 50-year loan, by contrast, extends exposure dramatically. Investors buying mortgage-backed securities from such loans would face decades of interest-rate risk. Borrowers would build negligible equity for a long time; for example, a borrower on a 50-year loan who sells after 12 years might have paid off only a few tens of thousands of dollars in principal on a loan that started near half a million dollars. A modest market downturn or a 6 percent decline in sale price could wipe out equity entirely, leaving borrowers underwater even after more than a decade of payments.

Regulatory and lender protections limit feasibility

Current qualified mortgage rules cap qualifying loan terms at 30 years in order to provide legal protections and reduce lender liability. Loans that exceed 30 years generally fall into the non-qualified category, which shifts more legal risk onto lenders and makes competitive pricing unlikely without explicit policy changes. To offer 50-year mortgages at rates comparable to 30-year loans would likely require government subsidies or a wholesale rewrite of mortgage law, effectively transferring risk to taxpayers or being hidden in higher home prices.

How a 50-year mortgage would likely appear in the Utah market

If a 50-year product appears, the most likely actors to push it will be developers and homebuilders who can bake financing incentives into the sale price or structure loans on a case-by-case basis. That design would make the loan effectively subsidized at the point of sale, pushing higher costs into purchase prices rather than lowering the true lifetime cost for buyers. For Utah buyers in high-growth cities such as Salt Lake City, Park City, and St. George, this could mean higher purchase prices and the illusion of affordability while lifetime interest and leverage increase.

Better policies to unlock Utah housing inventory

Stretching loan terms is not the only tool to improve affordability. Three pragmatic policy adjustments would more directly encourage supply and ease market frictions in Utah:

- Increase the capital gains exclusion for primary residences from $500,000 to $1,000,000 for married couples and index it to CPI. This would reduce the lock-in effect that keeps sellers off the market and is effectively an inflation adjustment to a decades-old threshold.

- Allow mortgage portability for primary residences so sellers can apply their existing mortgage terms to a new purchase when trading up. This would reduce the reluctance to list homes and free up inventory, especially in high-demand areas.

- Restore more generous mortgage interest deduction caps for new loans issued after a future date (for example, allowing deductions on up to $1.5 million of debt for new purchases). This would help buyers in higher-cost Utah markets without subsidizing legacy loans.

Local buyers should focus on unlocking inventory and controlling monthly expenses rather than relying on extreme term extensions. Simple cost reductions, careful budgeting, and shopping for competitive mortgage products can improve buying outcomes. For Utah-specific listings and market resources, visit https://bestutahrealestate.com

Practical guidance for Utah buyers and investors

For Utah families, young professionals, retirees, and investors, the following practical steps are recommended instead of opting into very long loans:

More Properties You Might Like

86 S 950 E, Hyde Park, UT

$774,900

Bedrooms: 6 Bathrooms: 4 Square feet: 3,544 sqft

LOOKING GLASS RD, La Sal, UT

$998,100

Bedrooms: 3 Bathrooms: 1 Square feet: 792 sqft

216 W RIDGE RD, Saratoga Springs, UT

$309,999

Bedrooms: 3 Bathrooms: 2 Square feet: 1,196 sqft

- Prioritize neighborhoods that match lifestyle needs and resale demand. High-demand locations hold value more reliably if inventory tightness eases.

- Maintain conservative leverage. A 30-year mortgage remains the market standard and often offers the best balance between monthly affordability and equity growth.

- Shop all financing options and understand amortization schedules. Smaller term adjustments, such as biweekly payments or slightly higher monthly contributions, can dramatically reduce lifetime interest without extending the loan 20 extra years.

- Consider portability and seller incentives when negotiating. A seller willing to accept assumable terms or temporary rate incentives may improve overall affordability without extending loan length.

Frequently asked questions

How much more affordable is a 50-year mortgage compared with a 30-year mortgage?

Realistic scenarios show a 30-year to 50-year shift improves qualification power by less than 8 percent. In contrast, moving from 15 to 30 years typically improves affordability by about 34 percent. Because longer terms carry higher rates, the practical affordability gain from 30 to 50 years is small.

Would a 50-year mortgage reduce lifetime interest paid?

No. Extending a mortgage to 50 years increases total interest paid because the borrower is in debt longer and more payments go to interest over the life of the loan. If lenders charge higher rates for longer terms, lifetime interest increases even further.

Could a 50-year mortgage make Utah housing more accessible?

Not meaningfully. The small monthly savings available on a 50-year loan do not offset higher lifetime costs, greater risk of negative equity, and reduced investor demand. Policies that increase inventory and reduce transactional barriers will have a more direct and durable impact on accessibility.

Why do investors dislike very long-term mortgages?

Investors bundle mortgages into securities expecting certain prepayment behavior. Very long-term loans expose investors to decades of interest-rate volatility and uncertain prepayment, reducing the attractiveness of these loans on the secondary market unless yields are substantially higher.

What solutions would help Utah specifically without extending loan terms?

Three targeted solutions include increasing the capital gains exclusion to one million dollars indexed to inflation, allowing mortgage portability for primary residences when trading up, and expanding the mortgage interest deduction cap for new loans. These policies would encourage more sellers to list homes and improve supply without creating long-term debt traps.